Anglage is a French term that means “chamfering” in English. That’s a term you’re probably more acquainted with. Regrettably, that still does not adequately describe what it is. What do the authors mean when they say a watch’s movement has “chamfered bridges” or “fine instances of anglage” in their reviews?

It’s actually a watchmaking method for making sharp right angles (where the flat top surfaces meet the perpendicular sides of components) seem more visually attractive. It serves no other purpose except to provide visual stimulation. These “corners” are filed down and beveled to a consistent angle, generally 45 degrees, across the whole edge.

While this may appear to be a simple task in principle, the chamfered edges must be uniform in angle and quality. The part’s form is enhanced by the polished chamfer. With tremendous power, however, comes great responsibility. When done by hand, anglage is not a technique that can be hurried. One tiny blunder or error may devastate an entire composition, rendering it useless.

That means hours of effort are wasted, and work on the replacement portion must restart from the beginning. As a result, anglage is one of the most delicate finishing techniques. Despite this, it is one of the most popular movements found in high-end watches.

Brands can eliminate most of the “by hand” stage thanks to improvements in contemporary machining and technology. They will never be able to completely eliminate the human touch. On a far bigger scale, modern machines can generate the initial bevels on numerous components during milling. This allows watchmakers from different manufacturers to concentrate on the finer points of finishing and polishing.

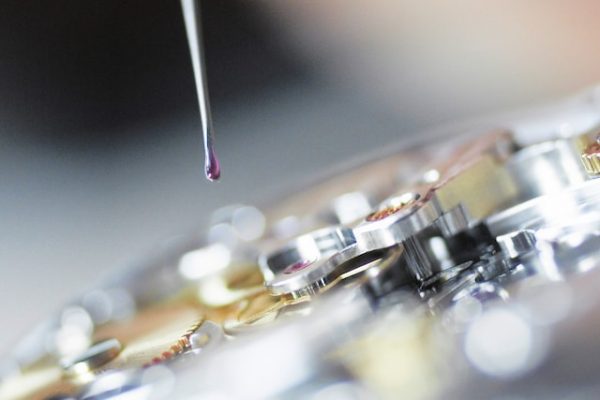

When doing anglage by hand, conventional equipment such as metal files or wood pegs with abrasive diamond pastes are used. Diamond pastes are used by watchmakers to provide a faultless polish and excellent gloss. They employ finer and finer grades of paste in succession, much like sandpaper, to create a mirror-like shine. Anglage is a time-consuming and precise process that needs a high level of dexterity and expertise.

As previously stated, existing machining processes make it difficult to completely eliminate the human touch from the Anglage process. Machines, for example, cannot finish the interior cut-outs on skeletonized pieces as well as a watchmaker. They unmistakably demand a hand finish. However, with continuing improvements in contemporary technology and production, who’s to say we won’t be in the same position in 50 years?

While I don’t believe hand-finishing will ever be completely obsolete (particularly in Haute Horlogerie), it will be interesting to observe how much more companies rely on machines in the future.